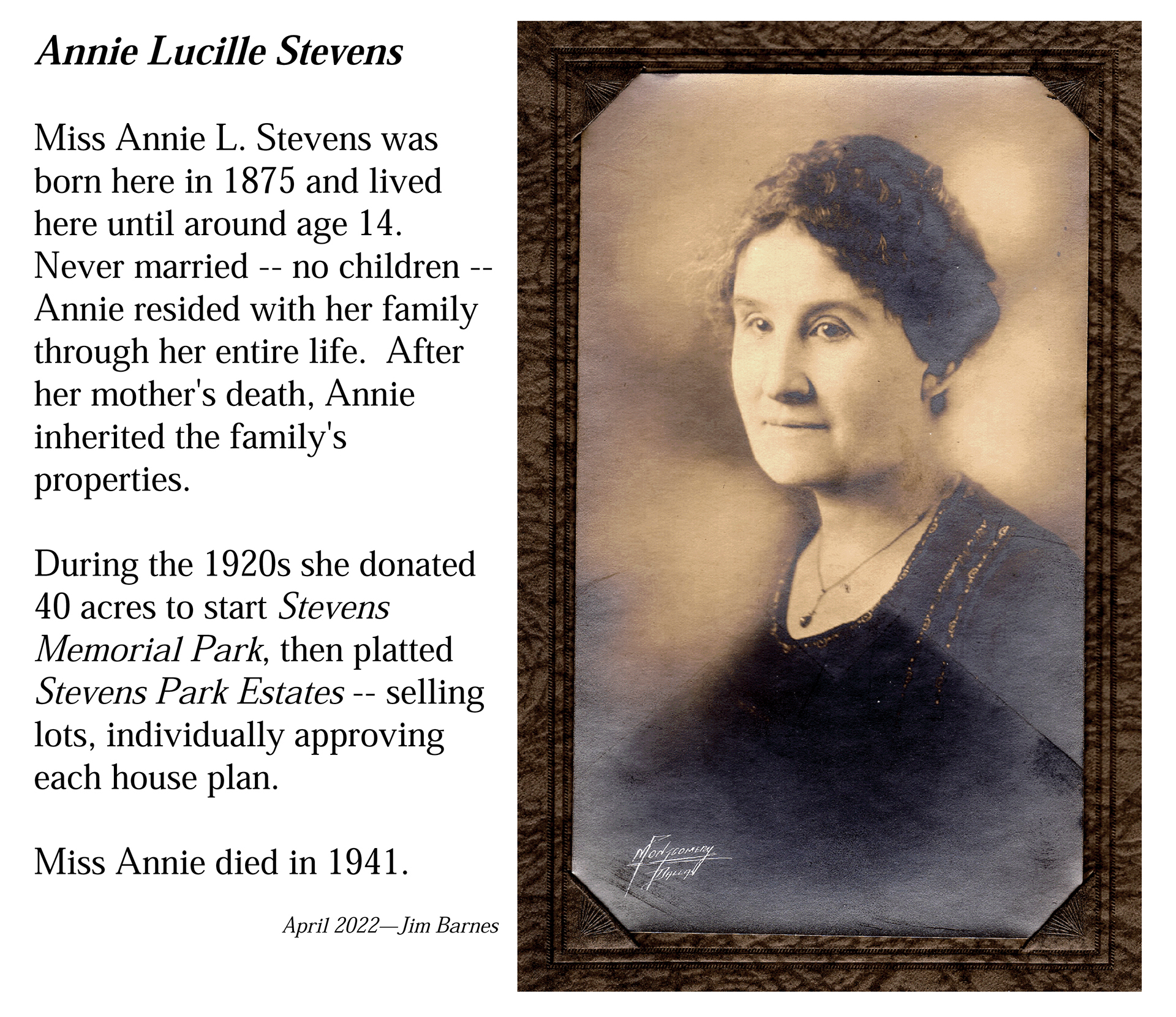

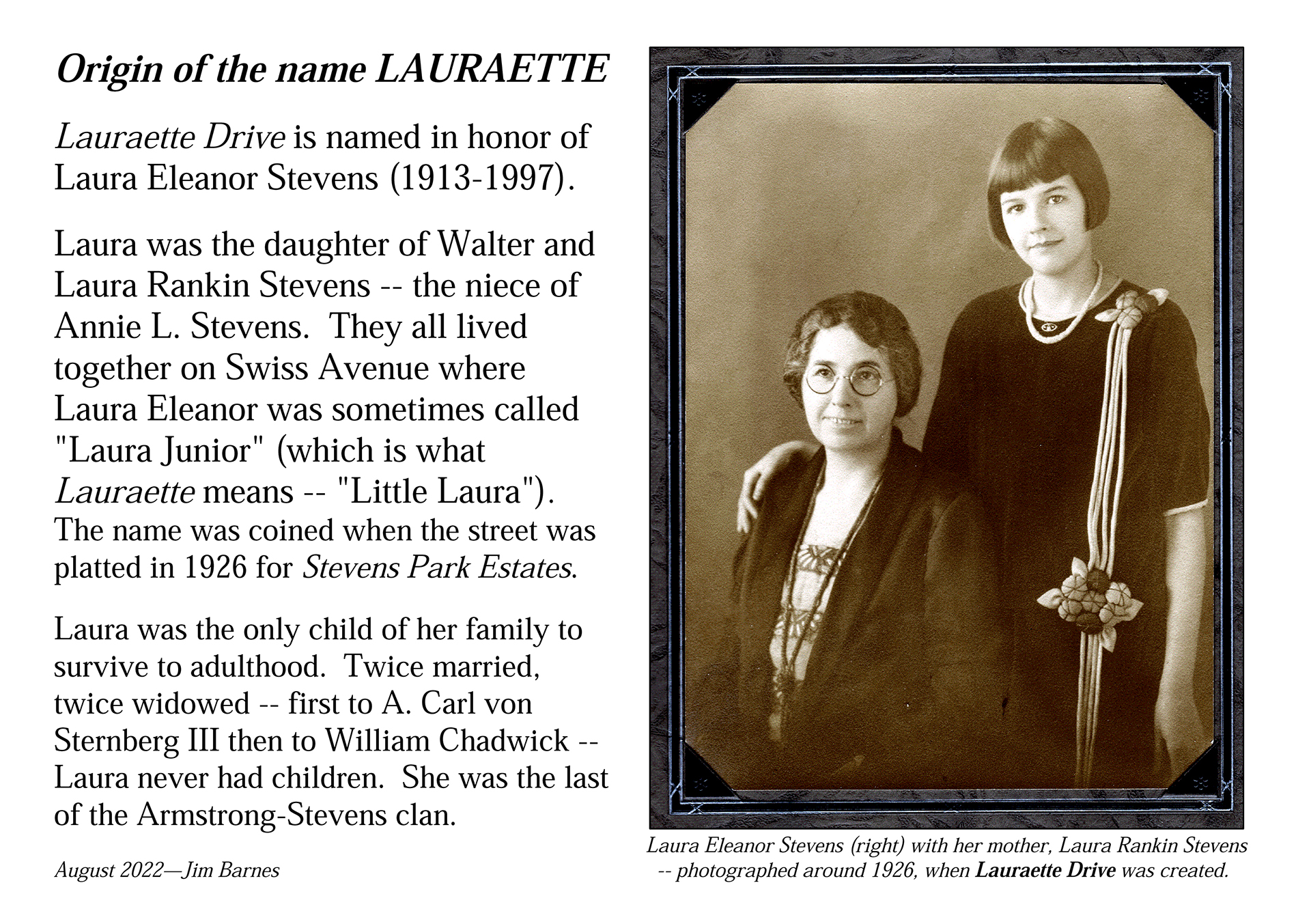

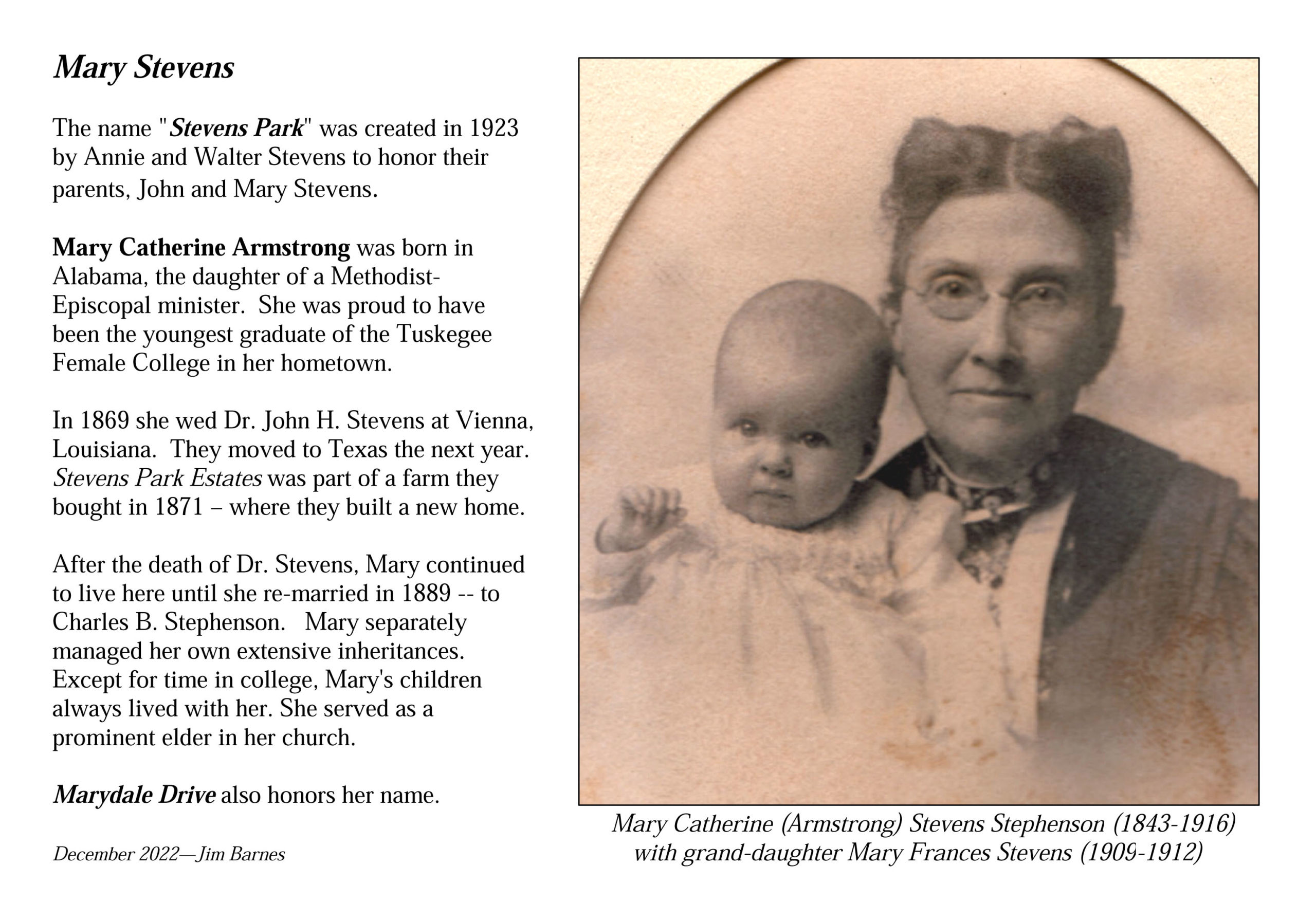

Located on green, tree-studded hills overlooking downtown Dallas, and bordered by the Stevens Park Golf Course, Stevens Park Estates is one of Oak Cliff’s gems. The neighborhood began development in 1925 from land owned by Annie L. Stevens, daughter of Dr. John H. and Mary Stevens, prominent Oak Cliff residents . Her development plans were assisted by her brother Walter (they always shared a home).

The original deed restrictions mandated that only two-story brick or stone structures be built on Colorado Boulevard and Plymouth Road, as well as all corner lots on interior streets. Unique circular play parks were incorporated at the ends of each block for the safety and enjoyment of the children. This commitment to children continues with the community designed and funded children’s park at Lauraette and N. Oak Cliff Boulevard. The homes were predominately constructed in the 1920s and 1930s, with development continuing to the present. Architecture is mostly English Tudor, Spanish Eclectic, and Colonial style, with some 1940s and 1950s ranch styles. Inside, many homes contain original features such as leaded or stained glass, plaster walls, period light fixtures, and colorful Art Deco baths with pedestal sinks. Home sizes range from quaint bungalows to large estates.

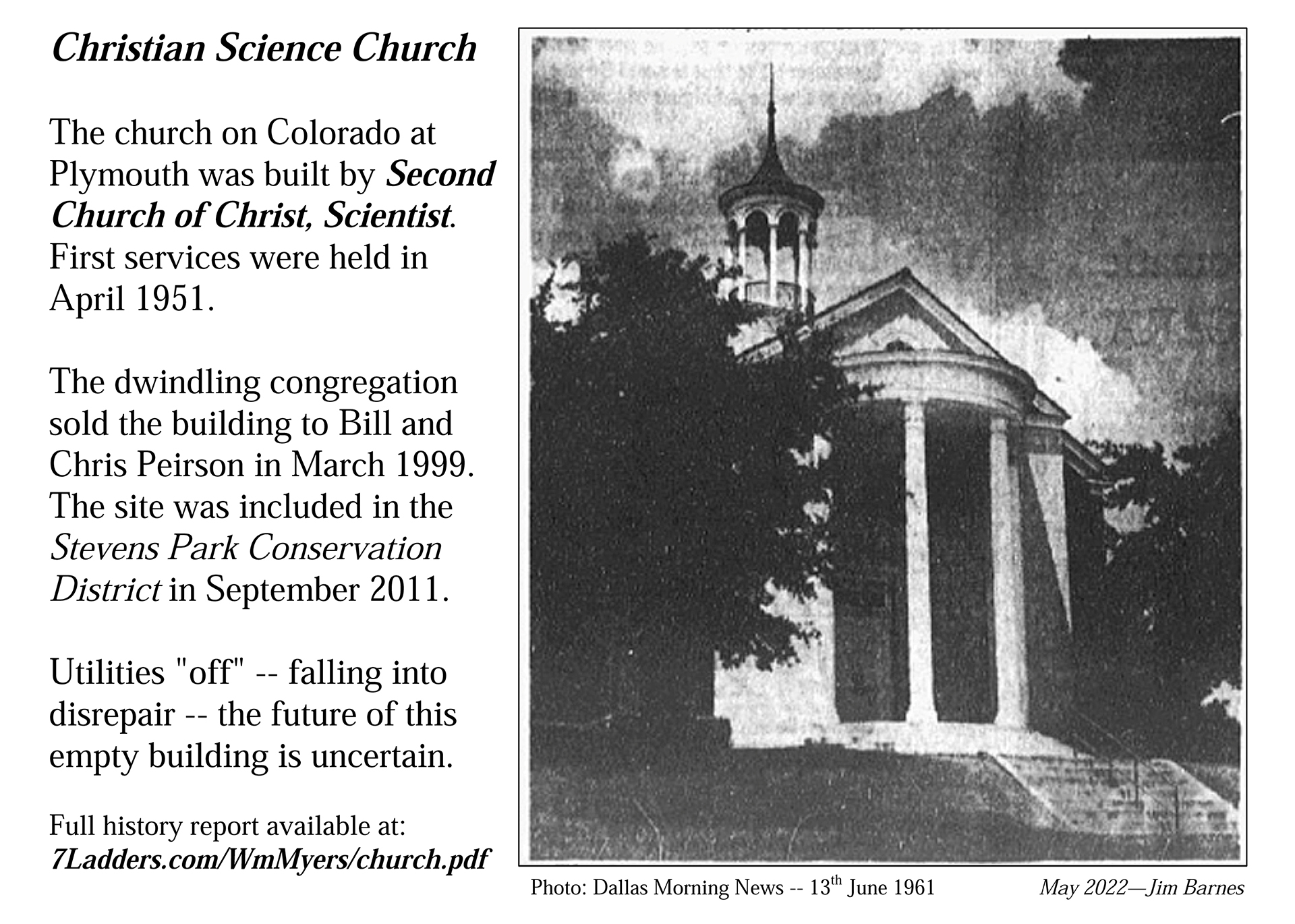

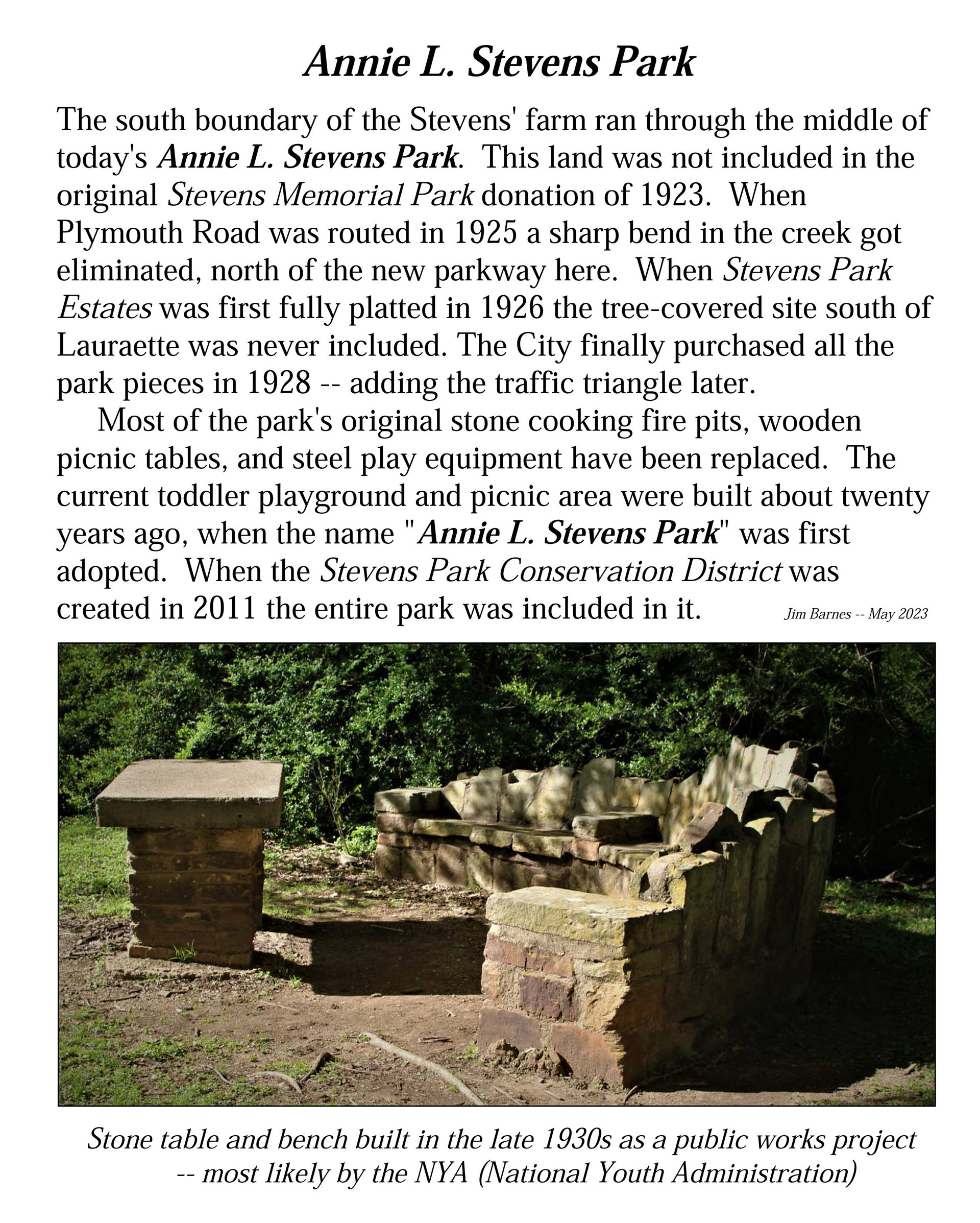

Stevens Park had an informal neighbor group through the ‘80’s. The Stevens Park Estates Neighborhood Association (SPENA) was founded in 1999 and was established as a non-profit 501 (c)-3 organization in 2001 with an all-volunteer Board. By-laws state that Board members are nominated and elected each January. In 2011 the neighborhood established a Conservation District to ensure the preservation of the homes and greenspace of Stevens Park Estates, including Annie L. Stevens Park.

The association plans and hosts monthly neighborhood gatherings during the year. This involvement combined with stable property values and elegant homes make Stevens Park Estates as sought after today as it was in our grandparents’ generation.